Interest rates in Australia are now lower than they were in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Why did the RBA cut interest rates in quick succession over the last two months?

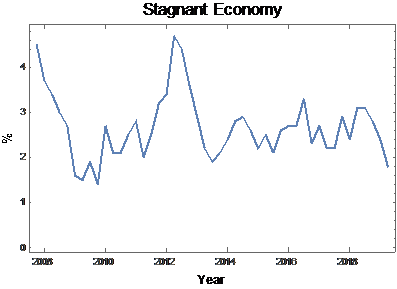

While the embers of growth inspired a series of interest rate hikes and quantitative tightening in the US, the Australian economy stagnated last year (refer to the chart below of year-on-year GDP growth). The Reserve Bank of Australia had little choice but to cut interest rates in the hope of stimulating growth.

Sources: Bloomberg, Arowana

As benchmark yields fall in Australia and remain very low elsewhere in the world, investors face the difficult challenge of finding a safe home for their capital that will provide them with an adequate rate of return.

Before we delve into these pockets of yield, it's instructive to gain some perspective on the malaise affecting the national economy.

We expect the national economy to decelerate―and to perhaps even contract―and we subscribe to the consensus view that an acceleration in growth is very unlikely over the next three years.

In a post-construction and post-resource boom world, with consumer discretionary spending at recessionary levels, all hope of a recovery in demand hinges on public expenditure and tax cuts.

It is unlikely that this fiscal stimulus will manifest in the form of significant new infrastructure projects in the near term. After all, the Coalition government's 2019 election victory was on the back of its touted fiscal discipline and a budget surplus in 2020.

It is also unlikely that China will come to the rescue of growth in Australia. In the lead-up to the GFC and its immediate aftermath, Chinese consumption, investment, and imports were a source of significant stimulus to the Australian economy. This insulated Australia from the global recession fallout. But since then, China's contribution to Australian growth has nearly halved.

Consumer spending is unlikely to support an economic rebound. The absence of growth in domestic and international demand for Australian goods and services has led non-mining corporates to focus on efficiency. This ruthless focus on costs has constricted wage growth. Consumer discretionary income is at recessionary levels despite steady unemployment. With house prices falling across most of Australia, consumer sentiment remains weak.

With these former pillars of growth now absent and unable to support the domestic economy, investors face the real prospect of a new normal of low benchmark rates of return on capital.

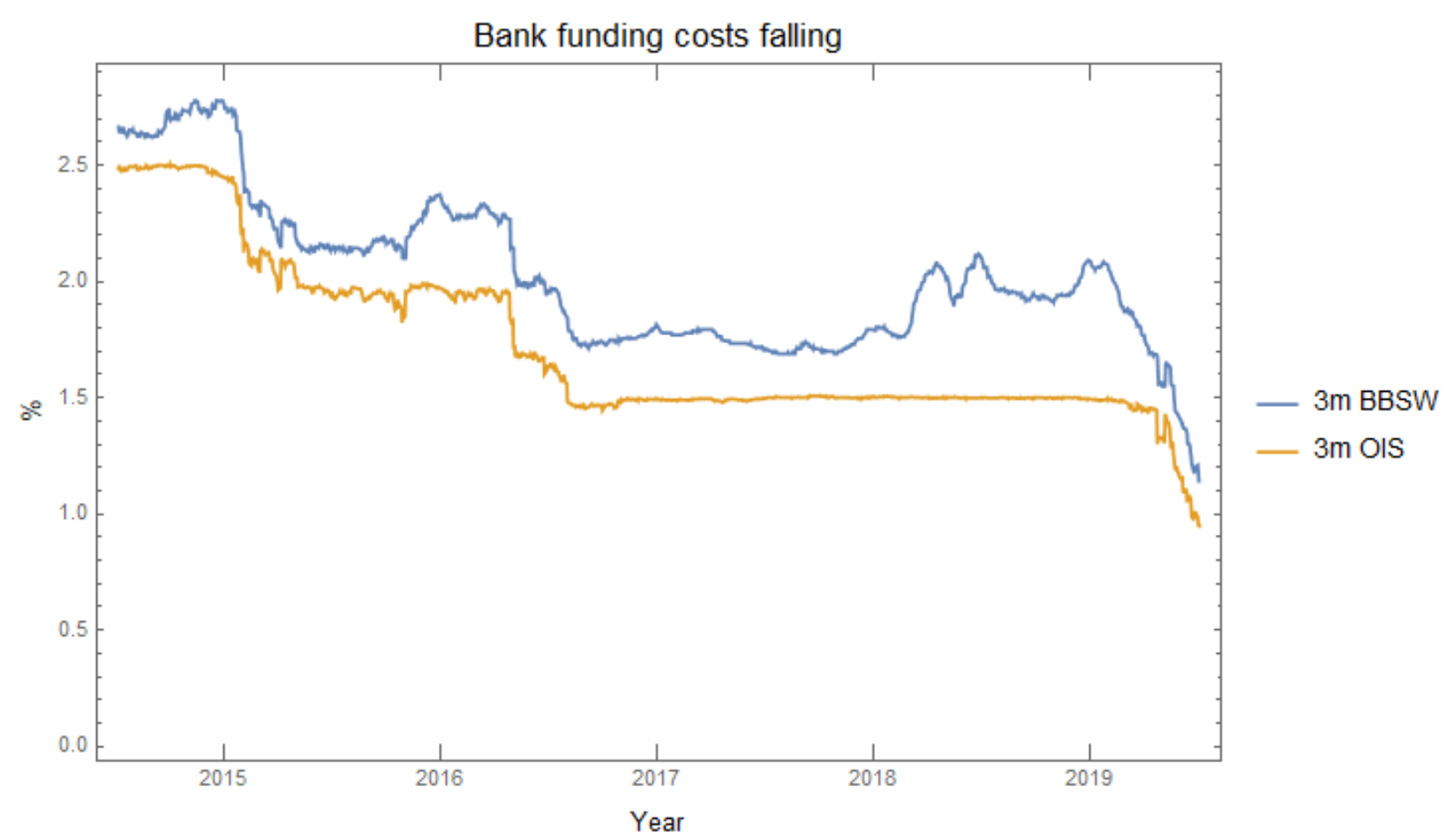

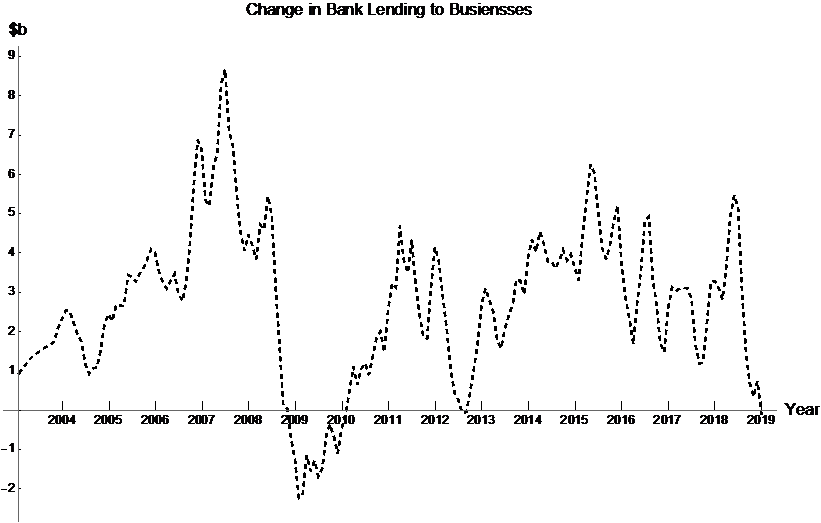

Against the backdrop of this slowing economy, bank funding costs remained high until the recent move by the RBA to cut rates. The high cost of funding and tight liquidity environment has seen the major Australian banks rationing capital to corporate borrowers.

Sources: Bloomberg, Arowana

The rate of increase in corporate funding saw its sharpest month-on-month decline since 2012 in May this year. Funding to corporates is now declining. Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions (ADIs) have been aggressive in their pursuit of reducing balance sheet exposure to this segment.

Sources: ASIC, Arowana

Capital has rotated to more Basel III capital-efficient asset classes such as residential mortgages and high credit rating-grade institutional borrowers and away from less efficient asset classes such as small private corporate borrowers.

Despite these challenges, most Corporate SMEs (CSMEs are defined here as businesses with revenues in the $20m to $50m) have not faced a particularly hostile borrowing environment yet. Our view is based on the 15 years of experience in investing in and operating SMEs and CSMEs in Australia, where anecdotally we have seen higher borrowing costs in the past than over the past 12 months. But let’s look at the evidence.

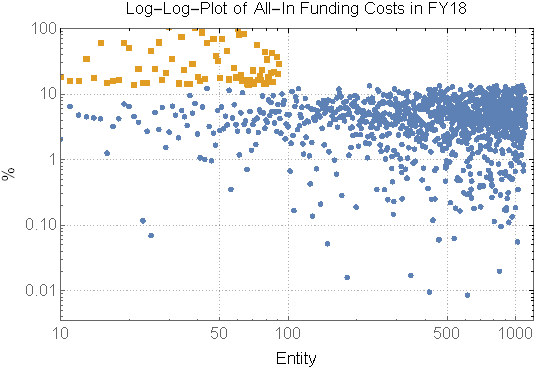

In FY18, there were two distinct classes of borrowers based on borrowing costs. The majority of CSMEs borrowed at interest rates that do not represent distressed or challenging capital market access conditions. A small cohort of borrowers did, however, pay significantly higher rates. The dot plot below visually segments these two categories. The orange dots signify borrowers that paid distressed funding rates; they were clearly in the minority.

The figure below indicates that the median borrowing cost of the clear majority (signified in blue in the chart below) of CSMEs was just under 5% whilst a small minority (orange data points in the chart below) of CSMEs paid a median rate in excess of 20%.

Sources: ASIC, Arowana

One possible reason for the continued favourable access to debt capital enjoyed by the CSMEs is that newly minted Fintech lenders―some with deposit-taking licences and 'high-yield' credit funds―are stepping into the breach left by the retreat of the major banks.

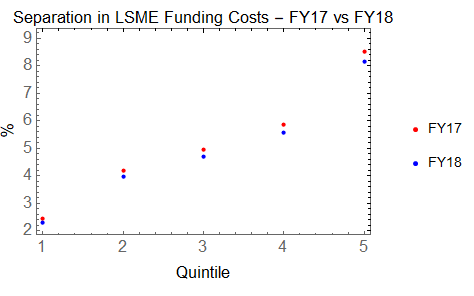

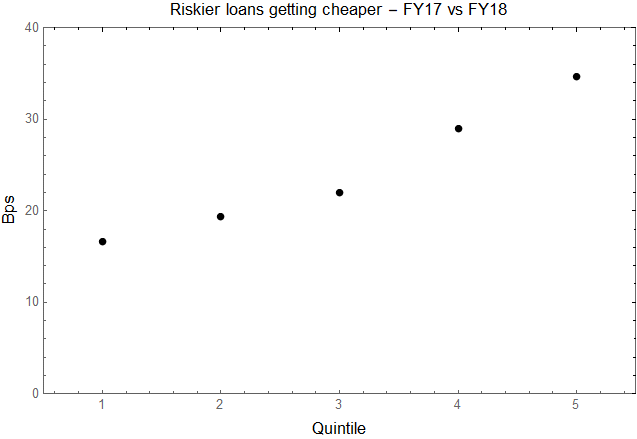

The chart below separates the funding of CSMEs into quintiles. Interestingly, it suggests that riskier borrowers have benefited the most from this disruption.

Sources: ASIC, Arowana

These high-risk borrowers have seen their funding costs fall by an average of 35bps over the FY17 and FY18 fiscal periods.

Sources: ASIC, Arowana

This calls into question the quality of assets being underwritten by these high-yield mandates and upstart Fintech disrupters.

In credit market parlance, the term ‘High-Yield’ refers to debt that is unrated and in some cases, to debt that is rated lower ‘BBB’ on the credit rating agency Standard and Poor’s rating scale.

Importantly, it is not a reference to a threshold rate of return on invested capital. So as an investor in a ‘High-Yield’ fund, you may be investing in very high-risk or distressed debt and earn low single-digit returns that don’t compensate you for the likely losses the fund will suffer as a result of investing in these high-risk assets.

To benefit from scale economies and tap into institutional debt capital markets, these high-yield mandates are sacrificing asset quality for safety in numbers. They are merely punting on the Law of Large Numbers in the hope that the asset quality of their portfolios will begin to mimic that of the broader asset class if the portfolio is large enough.

These large high-yield funds are merely aggregating debt from brokers and structured finance markets that the major banks have abandoned as too risky. What’s more, the “diversification” benefits―touted as the key mitigating factor to the risk of the underlying assets―will be of little comfort to investors in times of trouble. As we learned from the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, there is no safety in numbers for these assets, because in a downturn, the correlations of their returns rapidly converge.

Credit markets are littered with the failure of get-rich-quick strategies that try to manufacture returns in the absence of underlying cash flows. The legacy of this style of investing is the GFC that doomed the returns of almost every credit investment and those of its adjacent asset classes.

On the other hand, the fundamental credit disciplines of quantitatively and qualitatively unpacking the risks of each underlying investment and then structuring for downside scenarios, painstakingly analysing business, economic, and industry cycles, conducting primary research on both business fundamentals and capital market conditions is conducive to producing strong sustainable risk-adjusted returns that investors can bank on.

In a “Go Slow” economic environment, these two approaches to constructing high-yield portfolios are likely to have very divergent results. The temptation: to invest in asset-backed securities filled with diversified portfolios of high-risk or distressed debt, to accept very high leverage levels (leveraged loans), to forego setting covenants, to take no security, and to back businesses that would otherwise face external administration will inexorably lead to catastrophic levels of principal loss.

Credit funds that rely on heavy rotation and trading for Alpha generation carry the added vulnerability to capital loss from the volatility of credit spreads which, in a low-rate environment, have a material impact on the value of a security.

So where might investors look for sustainable returns against the backdrop of a “Go Slow” economic environment?

At Arowana, we have identified strong risk-adjusted returns in funding the revolving working capital needs of growing CSMEs with fundamentally stable underlying cash flows but have suffered a loss of liquidity because of the abrupt exit of the major banks.

As a B-Corp certified investment firm, Arowana overlays its bottom-up and top-down investment approach with an impact investing methodology that aims to assist and promote purposeful businesses to grow and flourish for the benefit of society and the environment.

These businesses create valuable assets in the form of receivables and inventory (with clearly observable market prices) and require equipment and vehicle fleets that can also be used as collateral for innovative collateralised debt facilities.

Most of these businesses have previously managed their operations to accommodate restrictive bank financial covenants yet have been unable to execute their growth mandates as a result of these constraints.

The private credit team at Arowana has developed an elegant structure that is designed to unlock the growth financing challenge for such businesses and at the same time deliver a sustainable and collateralised income yield to investors.