Our fifth anniversary as an LIC

The year ended 31 December 2019 marks the five-year anniversary of the Arowana being listed on the ASX. However, the Arowana Contrarian Value Fund (formerly the Arowana Australasian Value Opportunities Fund) was actually founded 10 years ago.

In the five years prior to its IPO, an audited ungeared return of 142.6% was achieved, representing an outperformance of 73.6% over the ASX/S&P 200 Accumulation Index which delivered a 69.0% return over the same period.

Since its IPO, CVF has returned 82.4% (12.8% annualised), outperforming the ASX S&P 200 Accumulation Index by 28.7%. We are pleased that the Fund has delivered outperformance during this time and over the last three years is in the top quartile of equity LICs on the ASX1, despite having no gearing and maintaining an average cash balance of 57.0%.

We look forward to continuing to deliver excellent value to our shareholders in the future and thank you for your ongoing support.

*The company is required to estimate the tax that may arise should the entire portfolio be disposed of on the above date and show the result per share after deducting this theoretical provision. Any such tax would generate franking credits, whose value would not be lost but rather transferred to shareholders on payment of franked dividends.

1 Source: ASX Investment Products. Included are only LICs that report three-year performance and have a market cap of >$30m. Performance data is three years to November 2019.

Global interest rates are very nearly zero and likely to stay low for the foreseeable future, according to the Chairman of the US Federal Reserve: “We are in a world of much lower interest rates, and I think it’s driven by long-run structural things and there is not a lot of reason to think that will change” – Jerome Powell, November 2019, Testimony before Congress on the US economy.

This prolonged low-rate environment and the accompanying adverse impact of low cash yields on lifestyle are forcing investors into assets that carry a higher level of risk.

So, what solutions to this yield dilemma does the Australian fixed income universe offer?

The chart below plots risk–reward characteristics of a broad spectrum of Australian fixed income investments. This discussion will focus on hybrid debt, leveraged finance, and private credit since they offer attractive rates of return relative to low cash like returns of the remaining debt categories.

At the most equity-like end of the spectrum, investors will encounter hybrid assets. The majority of these are issued by the regulated banks to meet ever-increasing regulatory Total Loss Absorption Capacity (TLAC) requirements.

Hybrids: Cheap Equity?

In July 2019, APRA confirmed―after releasing a discussion paper on the subject in 2018―that it “will require the major banks to lift Total Capital by three percentage points of [Risk Weighted Assets] RWA by 1 January 2024. APRA “expects the issuance of an additional three percent of RWA in Tier 2 instruments can be achieved in an orderly manner, and be maintained through varied market conditions.”

This means that over the next three to four years, investors should expect the volume of “loss-absorbing” instrument issuance in the form of Tier 2 hybrids to increase and to therefore “dilute” the value of these investments. These instruments are designated by the regulator to be near-equity equivalent capital that would be converted into equity at the regulator’s behest―likely at the first sign of domestic or global economic and financial system stress―to insulate the local financial and payment system.

They may have a preferred status over equity, but the veil that separates these instruments from the bottom of the capital structure is miniscule. To the banks, this is a cheap form of near-equity capital.

Leveraged Loans: CLOs are back in vogue

Leveraged loans―or are loans that either add to or result in borrowers carrying significant levels of debt―have expanded rapidly in recent years, especially in the US. Annual leveraged loan issuance in America has increased from US$100b in 2009 to $600b in 2018 [1] thanks to the abundance of cheap liquidity. Not surprisingly, the credit quality of these loans has concurrently weakened with leverage levels creeping from 3x-4x in 2009 to the pre-Global Financial Crisis levels of 6x-7x EBITDA (earnings before interest and tax)[2] and covenant protections have been eroded.

The situation in US markets is dire. A large swatch (55%-60%) of outstanding leveraged debt in the US is packaged into “collateralised loan obligations” or CLOs by private-equity firms, hedge funds, and others that slice up the loans and sell it to investors at significant premiums. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, over a third of leveraged loans refinance existing debt whilst the share of outstanding loans rated in the very risky ‘CCC+’ category has risen sharply[3]. This debt is not for growth funding―it’s just to kick the refinancing can just a little further down the road. In fact, a large component of the original debt emanates from merger and buyout funding and to pay private-equity firms’ dividends.

Private Credit: a sustainable yield payer

Regulated banks in Australia ascribe a 2% probability of loss[4] to their loans to small business[5] compared to 1% for residential mortgages. Thus, a rational investor would expect to earn at least twice the rate of return on a small business loan as they would on a residential mortgage.

But this is far from the case in Australia. While the three-year standard variable rate of a residential mortgage loan costs around 3%, expect to earn between 6% and 12% on senior secured business loans and over 16% on unsecured business loans.

So why is this debt so attractively priced for investors on a risk-adjusted return basis? One reason is that it’s a market that has traditionally been serviced exclusively by the banks. Recently imposed higher regulatory capital risk weightage towards corporate loans has prompted a rapid withdrawal of bank-lending to this sector, leaving a void that is being filled by alternate lenders. The shortage of capital supplied to the segment has resulted in a spike in yields.

Why are these yields sustainable?

The moat that restricts the supply of capital flow to this asset is the relative difficulty of originating and structuring transactions and assessing the credit worthiness of these borrowers relative to the level of fees available to pay for the requisite level of diligence due to the smaller deal sizes associated with this segment of the market.

The concentration of banking in Australia supported the banks’ profitability of small business lending through the sheer scale of operations. That profitability has now been swept away by the increase in relative regulatory capital weighting.

[1] Economist, What are leveraged loans?, 11th Jan 2019.

[2] S&P, Leverage on US LBOs Hits Highest Level Since Financial Crisis, 3rd October 2017. S&P, Leverage Creep: With EBITDA Adjustments/Synergies, Risky Loans Grow Riskier, 23rd October 2018. S&P, as leveraged loan downgrades mount, CLOs cast wary eye on triple-C limits, 1st November 2019

[3] Ibid

[4] Connolly and Jackman, “The Availability of Business Finance”, RBA December Quarter 2017

[5] The SME categories in APRA’s capital framework include businesses that have reported consolidated annual sales of less than $50m

DDLS, Australia’s largest provider of corporate ICT and cybersecurity training, today introduced a course in cybersecurity that will take students with no ICT background to three internationally-recognised cybersecurity certifications in less than six months.

The Certified Cybersecurity Professional course will be delivered by the Australian Institute of ICT (AIICT), a division of DDLS, and will provide an interactive online experience that aims to turn people with zero industry experience into job-ready, frontline Cybersecurity Analysts.

Jon Lang, CEO of DDLS, commented: “Unemployment levels in cybersecurity are at 0%, and there is huge unmet demand. In Australia alone at present, there are almost 1,000 cybersecurity jobs advertised on the employment website, Seek.”

According to the November 2018 update to Australia's Cyber Security Sector Competitiveness Plan, Australia needs another 2,300 cybersecurity workers, and that number is expected to grow to 17,600 by 2026. (ISC)2, the world’s largest not-for-profit association of cybersecurity professionals, estimates a worldwide skills gap of 2.93 million, with 2.14 million of these in the Asia-Pacific region.

Learn more about the Certified Cybersecurity Professional course.

VivoPower is pleased to announce that it has sold its remaining Sun Connect portfolio of operating solar projects for A$1.6 million. Over the life of VivoPower’s investment, the sale represents a 2.0x multiple of invested capital and an unlevered IRR of 20.1% before tax.

The company is equally gratified that its Australian critical power services business, J.A. Martin Electrical Pty Ltd, has been awarded two additional contracts for solar farm construction worth A$4.4 million.

To review a copy of the VivoPower announcement, please click on the link below.

As business owners, Arowana understands first-hand the challenges that companies face when trying to secure debt capital to expand. If your business has not reached $100m in revenue yet, you’re probably struggling to access funding for growth.

It’s a chicken and egg type of problem: to achieve their growth aspirations, businesses need to secure the working capital required for such growth. Traditionally, this capital requirement must be met through an equity injection from the sponsors and owners.

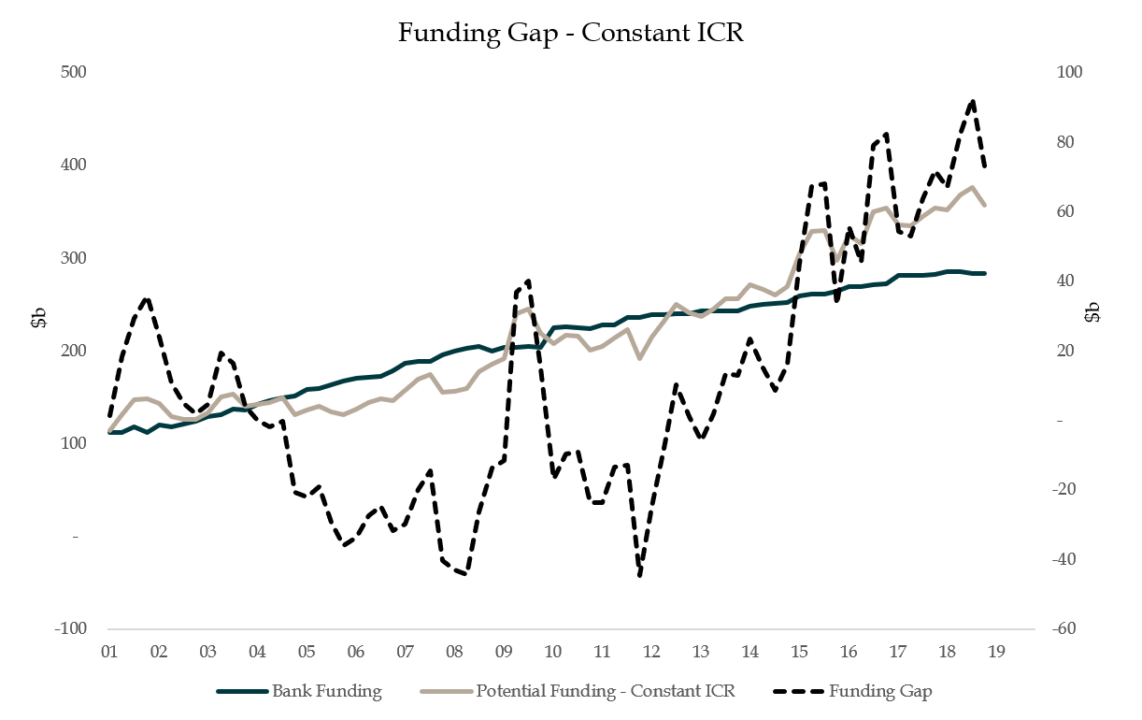

However, there are other funding mechanisms that bypass the banks, and are increasingly prevalent in providing much-needed finance to help SMEs achieve ambitious growth targets while addressing a $70bn funding gap.

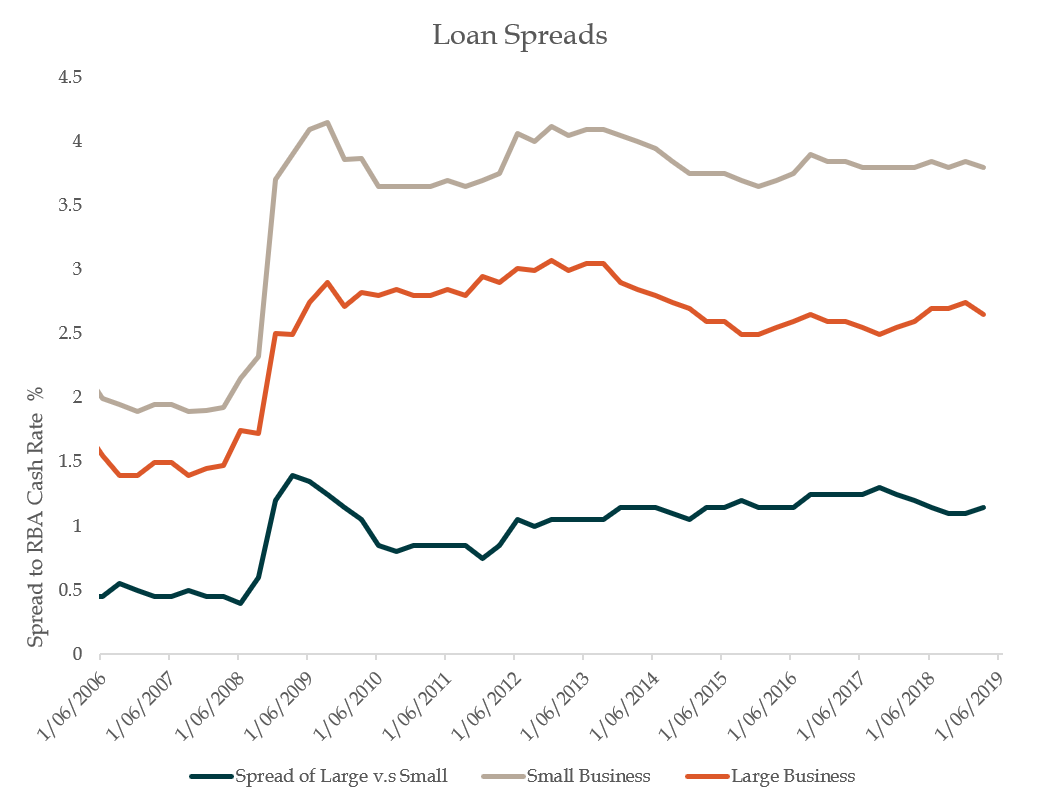

Many of our businesses are funded purely with equity. Traditional sources of debt funding, such as loans from the major banks, have been reserved for large businesses that turn over more than $100m. Businesses of a smaller scale must rely on mortgaging real property security to attract lenders. The chart below of bank lending to large and small business supports this thesis.

This is not just a problem that businesses face with the major banks. Regional banks and challenger banks are vying for a client base that fits the real property security mould. Cashflow-based loans for small business come in very small packages, and/or subject the borrower to very restrictive covenants.

Source: RBA, Arowana

Once a business surpasses a revenue threshold of $100m, there is no shortage of bank loan funding, and banks are also willing to take businesses to the domestic high-yield debt market. The high-yield debt market is funded by institutional investors, such as Superannuation Funds and Investment Managers, that buy corporate loans on behalf of their clients. Banks will usually arrange, underwrite, and distribute the high-yield debt instruments of their large borrowers.

Investors in syndicated debt and large corporate credit are not supplying liquidity to the small business community; they are merely reducing the cost of funding for large businesses and adding to the fees and costs that investors and borrowers must bear, with less than incremental contributions to both these communities.

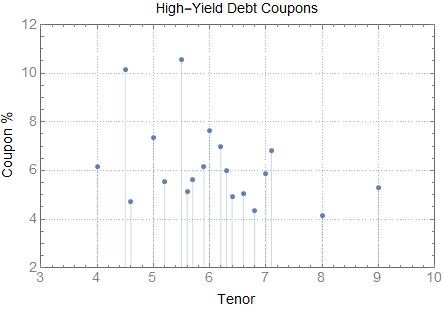

High-yield debt issuance, mostly in the Syndicated Loan format, supplied $3.4b p.a. over the past five years. Most of this debt was provided to large corporate borrowers.

Source: Bloomberg, Arowana

Debt in the high-yield market has attracted an average rate 7% p.a. for tenors between four to six years, while bank debt, traditionally amortising over four to six years, has an average rate of 4.5% p.a. over the past five years. Small businesses―those that borrow less than $2m―have a comparable bank funding cost of 1% p.a. more than large business.

Source: Bloomberg, Arowana

Source: RBA, Arowana

The debt capacity of these businesses (using constant Interest Cover Ratio - ICR) suggests that the funding shortfall plaguing small business currently exceeds $70b. In estimating this funding shortfall, Arowana applied a constant debt capacity to contemporary borrowing costs and profitability[1]. This estimate is corroborated by research independently conducted by Macquarie Bank[2].

Source: RBA, Arowana

In November 2018, the Morrison Government announced a plan to bridge this funding gap with a $2b Australian Business Securitisation Fund[3] that will invest up to $2 billion in warehousing and the securitisation market to improve the access that small businesses have to debt funding. The new fund will be administered by the AOFM. In February 2019, the government introduced legislation to implement the fund. The fund will target investment in securities issued by warehouses alongside other private sector investors. These warehouses provide funding to smaller banks and non-bank lenders for loans extended to small business.

On the private funder side of the fence, asset-based fintech firms are taking the lead on meeting this pervasive funding gap.

Closing the gap: Asset-based Lenders

Asset-based lenders extend loans to small businesses secured by tangible assets such as debtor ledgers, vehicles, equipment, and inventory. In 2018, invoice financiers alone have funded close to $87b of assets[4] for small and large business in Australia.

Working capital funding of this nature is ideal for businesses with high-growth aspirations as it removes the obstacle of dynamic asset funding that is a prerequisite for that growth.

Debt facilities offered by these entities will typically involve revolving credit lines and cash flow loans that release liquidity from and equipment, property, or self-extinguishing assets such as debtors.

Debt facilities related to self-extinguishing assets such as debtors, fluctuate with the asset balances that they fund and so reduce the funding risk for borrowers. This harmonisation of the timing of assets and liabilities reduces liquidity risk for borrowers and lenders with additional comfort.

On a micro level, this type of funding provides a critical avenue by which individual SMEs can access finance. Meanwhile, on a macro level, it is beginning to address a massive funding gap that is slowing down some of the country’s most promising SMEs, which are the lifeblood of the Australian economy.

[1]

[2] Macquarie Bank Research, “The Computer Says Yes”, March 2015.

[4] FCI, Annual Review 2019, AUD/EUR 60 cents as at 26/08/2019

It’s no secret that SMEs are struggling to access credit, thanks to a perfect storm in lending markets.

We estimate an SME funding gap of over $70B. The Hayne Royal Commission, global regulations requiring banks to hold more capital, and a slowing economy, have all contributed to traditional lenders tightening their purse strings.

What’s less well-known is the plethora of emerging alternative financing options for SMEs―and how to find the right one for your business.

Firstly, it helps to understand how credit markets work. Over 70 per cent of the debt capital supplied to SMEs comes from regulated banks. Banks measure the risk of a commercial loan by assessing the risk of default and the subsequent potential loss.

Default risk is the risk that a borrower does not service their debt in full and on time. This risk is closely linked to the debt capacity of SMEs and their ability to withstand industry shocks and defend their market share.

Banks and rating agencies typically use industry benchmarks of operating and financial metrics to anchor their credit risk assessments. This means, for example, having a benchmark figure for the expected profitability of construction companies. The finances of the business will be reviewed against this benchmark and rated accordingly.

But benchmarks present challenges for SMEs, which tend to face greater intensity of competition and greater vulnerability to industry downturns than larger businesses. Their relatively weak bargaining power also exposes them to risks with supply chain funding, bottlenecks, and customer and market segment concentration.

As such, SMEs often compare unfavourably to the benchmarks, which is exacerbated by a lack of quality collateral. If collateral is connected to the performance of the business, it is viewed as lower quality as its value is likely to drop if the business is struggling. This contrasts with property, the value of which is likely to be driven by independent factors.

SMEs without quality collateral that operate in sectors that exhibit a high level of cyclicality and intensity of price-based competition, and have little differentiation in product or service―such as construction or hospitality, for example―will struggle to access funding from traditional lenders.

Unfortunately, most SMEs face this predicament. So, what can a small business that can’t access bank funding whilst facing onerous payment terms from large customers and suppliers do to maximise their opportunity for securing credit?

Thankfully, alternative creditors are entering the market to meet this need and tap into the $70B opportunity. But the variety of new players can itself be challenging, making it tricky for SMEs to choose the right lender.

As a first step, SMEs should consider what the financing is for. Is it a short-term fix to cover salaries? If so, the speed of an online lender may be an attractive option, with the downside of high-interest rates mitigated as the loan will be quickly repaid.

Or is financing required to scale the company over time, requiring a larger sum and a deep understanding of the business? In that case, it makes sense to find a strategic partner who can provide funds while adding value with advice or other forms of support.

Payment terms are a major issue for SMEs, but there is innovation in this space too, with financiers willing to lend against the value of outstanding invoices.

Importantly, SMEs must understand what potential funders are looking for and the type of financier that will add the most value to their business.

This article was originally published on Inc.com.

Kevin, Chin, our CEO, was asked about the process of becoming a B Corporation by Inc.com. This is what he shared.

How did you learn about becoming a B Corporation?

I first learned about B Corporations―the B stands for beneficial―in September 2016 when, during a conference, my preferred session was full, so I walked into a session about B Corps. I knew nothing about them beforehand. I walked out convinced that B Corps would become a gold standard certification, that the ethos of B Corps aligned with our core values, and it was where I wanted to take my company.

Certified B Corporations are for-profit companies that meet the highest standards of verified social and environmental performance, governance, transparency, and legal accountability. The ultimate goal is to balance profit and purpose, using good. To become certified, a rigorous due diligence assessment is conducted by the B Lab organisation, a non-profit certification body. In order to achieve and preserve certification, companies must attain a minimum score for environmental, social, and governance performance.

What's the difference between a B Corp and a company that commits to responsible corporate citizenship?

Most companies do set out to be responsible corporate citizens. The vast majority also have a primary purpose of maximising shareholder returns. With the increasing myopia of shareholders, this creates pressure on corporate leaders to make a profit at any cost―sometimes manifesting in behaviour that is not conducive to sustainability and long-term success.

A case in point is Boeing, whose 737 Max aircraft was rushed into service over concerns about competition from Airbus adversely impacting annual profits. This led to the deaths of 346 passengers.

A key difference with B Corps is that they are required to codify in their company constitution that their ultimate purpose is to operate their business as a force for good and for the benefit of all stakeholders―not just shareholders.

Another key difference with B Corps is that they legally commit to an annual assessment of environmental, social, and governance performance. Failure to uphold standards could result in an embarrassing loss of accreditation. By contrast, companies that commit to being responsible corporate citizens are generally not held accountable by an assessment mechanism.

In that case, why did you voluntarily put your company through the hassle of becoming a B Corp?

As our company approached its 10th anniversary, I wanted to effect a major cultural transformation to align with our core purpose of building sustainable companies. This core purpose necessitates a long-term horizon. However, at the time, our culture was overly focussed on short-term remuneration, where people essentially lived for the annual bonus day. This was a legacy of the company's private equity firm background where an annual bonus mindset defines culture.

As the Boeing example illustrates, such misalignment can be dangerous and is not conducive to building companies over the long term. I realized the fundamental incompatibility between what we were already becoming―an organization that invests in, owns, fixes, and scales up companies―versus our private equity roots of flipping companies for profit.

So, my stumbling across B Corps was serendipitous. I felt that becoming a B Corp would be the perfect catalyst to drive cultural change.

In addition, I liked the fact that B Corp assessment would provide a robust, independent review of our systems, processes, and governance architecture. Furthermore, it provides a methodology and scorecard to assess these elements on an ongoing basis.

What were some unanticipated issues you confronted?

B Corp accreditation was much harder and took far longer than anticipated! This was partly because we have multiple businesses across four continents, but also because the assessment process is rigorous. It took 15 months; we were accredited in May 2018.

It was also a more powerful catalyst than I anticipated for driving cultural transformation. For example, a forensic review of our governance architecture, including the quality of and compliance with company policies, led to a handful of senior employees being exited. We experienced significant cultural turbulence, complete with toxic behaviour designed to disrupt and try to destroy the organisation.

What would you share with leaders contemplating B Corp accreditation?

Strong group revenue growth with EBITDA improvement

Group balance sheet strengthened with increase in net cash

VivoPower results improved due to strong growth in Aevitas businesses

EdventureCo results significantly ahead of budgets as are strategic plans

Highlights from AWN's FY2021 results:

Further information:

AWN FY 2019 Annual Results Investor Presentation

VivoPower International PLC (“VivoPower” or the “Company”) is changing its financial year end to 30 June, with effect from 30 June 2019, This is being done to deliver on further productivity and cost savings by harmonising with the financial year end of its ultimate parent entity, Arowana International Limited, This Chairman’s Statement is accordingly for the three month period ended 30 June 2019. The key developments during this period were as follows:

Further information:

VivoPower FY2019 ending 30 June 2019 Annual Report

We are pleased to announce that DDLS Australia Pty Ltd, which is the largest Corporate IT training provider in Australia, has officially launched training in the Philippines under its joint venture with Aboitiz Equity Ventures, Inc. (PSE:AEV).

With over 1.3 million people employed in the Philippine Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) sector, employers are looking to move their workforce up the value chain with core skills in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) courses that include cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and data science.

This bodes well for DDLS Philippines, given the strong desire from the Philippine government, industry, and private sector to continually upskill and future-proof their workforce.